Quick Overview¶

This section provides a quick overview of the PyRat library and its workspace structure.

Contents of the PyRat Library¶

In PyRat, we manipulate two main types of files:

Games: These are Python scripts that define a game using the PyRat API. They are stored in the

gamesdirectory of the workspace. These scripts typically import the PyRat library and use its functionalities to create a game environment, with players, mazes, and game objectives.Players: These are classes that define the behavior of a player in the game. They are stored in the

playersdirectory of the workspace. Contrary to games, players are not scripts but rather Python classes that inherit from thePlayerclass provided by the PyRat library. They implement methods that define how the player interacts with the game, in particular how it moves and reacts to the game state.

The PyRat library provides a set of modules that can be used to create and manipulate mazes, players, and games. You can import these modules in your Python scripts to use their functionalities.

How does PyRat Work?¶

Game Objectives¶

In a PyRat game, the goal is to collect pieces of cheese in a maze. The maze is represented as a grid, and players can move through the maze by iteratively choosing directions.

The game can be played with one or more players. Depending on the number of players, the winning condition may vary:

Single Team: The player(s) must collect all cheese pieces in the maze.

Multiple Teams: The player(s) must collect more cheese pieces than the other teams.

Starting a PyRat Game¶

To start a PyRat game, you typically follow these steps:

Open VSCode, and add your

pyrat_workspacedirectory in your VSCode workspace.Open the file

sample_game.pyin directorypyrat_workspace/games/.Make sure VSCode is using your virtual environment where PyRat is installed.

Run

sample_game.py.

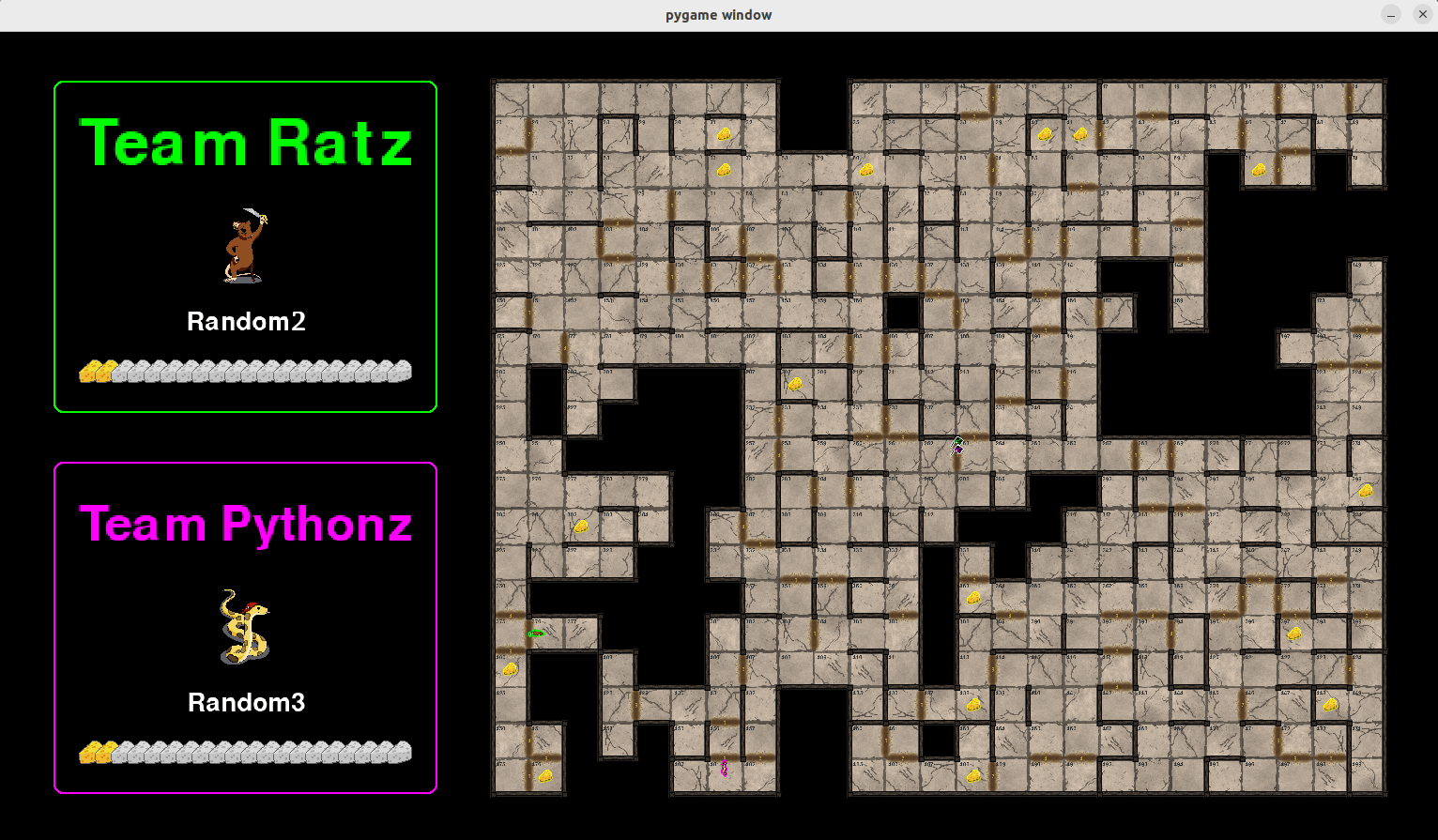

You should see something like this:

Elements of the Interface¶

In the PyRat interface above, you can see the following elements:

Scores Area: On the left part of the screen, you can see the scores area, that shows which players are engaged in the game, how they are grouped in teams, and their current scores. In this example, we have a match between two teams, respectively named Team Ratz and Team Pythonz. Here, each team contains a single player, respectively

Random2(with the skin of a rat), andRandom3(with the skin of a snake).Maze Area: On the right part of the screen, you will find the maze, in which the game takes place. The maze lies in a rectangle of dimensions

maze_widthxmaze_heightthat may have some holes. Cells are numbered from0tomaze_width * maze_height - 1. You can also see some walls, and some cells separated with mud. The former cannot be crossed, and the latter require the number of turns indicated to reach the cell on the other side.Game Elements: Characters and pieces of cheese are rendered in the maze at their current location. Note however that the GUI is not synchronized with the actual game, to be able to visualize it nicely. Therefore, if you choose to print your current location in your code, you will not see the same cell as in the GUI. The color around players is there to indicate their teams. You may also notice some small flags in the middle of the maze, which indicate the starting locations.

Needed Elements in a Game¶

A PyRat game typically needs the following elements:

Game Settings: A description of the game elements, such as the maze dimensions, the number of pieces of cheese, density of walls, etc. These elements are defined when instantiating the game object object in the script.

Players: Classes that define the behavior of players in the game. These classes inherit from the Player class and implement methods that define how the player behaves in the game.

In the game script, you create your game by instantiating a Game object with desired settings. Then, you create instances of your player classes and add them to the game. Finally, you can start the game loop where players take turns to make moves until the game ends.

# First, let's customize the game elements

# This is done by setting the arguments of the Game class when instantiating it

# In Python, we can also create a dictionary `d` with these arguments and pass it to the Game class using `game = Game(**d)`

# This can be convenient for code organization and readability

game_config = {"mud_percentage": 20.0,

"cell_percentage": 80.0,

"wall_percentage": 60.0,

"maze_width": 13,

"maze_height": 10,

"nb_cheese": 5}

# Instantiate a game with specified arguments

game = Game(**game_config)

# Instantiate players with different skins, and add them to the game in distinct teams

player_1 = Random2(skin=PlayerSkin.RAT)

player_2 = Random3(skin=PlayerSkin.PYTHON)

game.add_player(player_1, team="Team Ratz")

game.add_player(player_2, team="Team Pythonz")

# Start the game

stats = game.start()

pprint.pprint(stats)

You can also build more complex game scripts, for instance by running multiple games in a loop to gather statistics. This can be helpful to compare multiple algorithms for a same objective, or to test the robustness of a player against different mazes.

Phases of a Game¶

A PyRat game consists in four phases, that we illustrate below using the code in TemplatePlayer.

Before the Game Starts: When players are instantiated in the game script (see above), the constructor of the player class (

__init__()method) is called. This is where you can define attributes or perform any setup that is needed before the game starts. However, you do not have access to the maze or the game state at this point.def __init__ ( self, *args: object, **kwargs: object ) -> None: """ This function is the constructor of the class. When an object is instantiated, this method is called to initialize the object. This is where you should define the attributes of the object and set their initial values. Arguments *args and **kwargs are used to pass arguments to the parent constructor. Args: args: Arguments to pass to the parent constructor. kwargs: Keyword arguments to pass to the parent constructor. """ # Inherit from parent class super().__init__(*args, **kwargs) # Do what you want here

Preprocessing: When the game starts, players are given some time to optionally make computations and prepare their strategies. The duration of this phase can be set in the game settings using the

preprocessing_timeargument. During this phase, players can analyze the maze, plan their moves, and prepare for the game. To describe what to do during this phase, you should implement thepreprocessing()method in your player class.@override def preprocessing ( self, maze: Maze, game_state: GameState, ) -> None: """ *(This method redefines the method of the parent class with the same name).* This method is called once at the beginning of the game. It can be used to initialize attributes or to perform any other setup that is needed before the game starts. It typically is given more computational resources than the ``turn()`` method. Therefore, it is a good place to perform any heavy computations that are needed for the player to function correctly. Args: maze: An object representing the maze in which the player plays. game_state: An object representing the state of the game. """ # Do what you want here

Note that this function receives two arguments: the

mazeand thegame_state:The maze is a particular type of graph (in details, class

Mazeinherits from classGraph). It contains information about the walls, holes, and other elements of the maze. It also provides methods to access the neighbors of a cell, check for mud, etc. We advise you to read the documentation of theMazeclass to understand how to use it.The game state is an object that contains information about the current state of the game, such as the players’ positions, scores, and remaining cheese. We advise you to read the documentation of the

GameStateclass to understand how to use it.

Player Turns: After the preprocessing phase, the game enters the main loop where players take turns. Each player has a limited amount of time to make a move, which is defined in the game settings using the

turn_timeargument. During this phase, players can analyze the maze, check their current position, and decide on their next move. To define what a player does during its turn, you should implement theturn()method in your player class.@override def turn ( self, maze: Maze, game_state: GameState, ) -> Action: """ *(This method redefines the method of the parent class with the same name).* This method is called at each turn of the game. It returns an action to perform among the possible actions, defined in the ``Action`` enumeration. It is generally given less computational resources than the ``preprocessing()`` method. Therefore, you should limit the amount of computations you perform in this method to those that require real-time information. Args: maze: An object representing the maze in which the player plays. game_state: An object representing the state of the game. Returns: One of the possible action, defined in the ``Action`` enumeration. """ # Do what you want here # Return an action return Action.NOTHING

As in the preprocessing phase, this function receives two arguments: the

mazeand thegame_state. The game state is updated at each turn, so you can use it to check the current position of the player, the scores, and the remaining cheese.Note that the

turn()method must return an action, which is one of the possible actions defined in theActionenumeration. Check the documentation of theActionenumeration to see the available actions.Postprocessing: When the game ends, players can perform some final computations and cleanup. This phase is optional and can be used to gather statistics, save results, or perform any other final tasks. To define what a player does during this phase, you should implement the

postprocessing()method in your player class.@override def postprocessing ( self, maze: Maze, game_state: GameState, stats: dict[str, object], ) -> None: """ *(This method redefines the method of the parent class with the same name).* This method is called once at the end of the game. It can be used to perform any cleanup that is needed after the game ends. It is not timed, and can be used to analyze the completed game, train models, etc. Args: maze: An object representing the maze in which the player plays. game_state: An object representing the state of the game. stats: A dictionary containing statistics about the game. """ # Do what you want here